How AI Works After Training

Part 3 of My AI Series (including some visual aids)

Hello all.

Welcome and welcome back.

If you haven’t read my last article, I think you would be better off reading it before reading this one, but you have agency - so you can choose. I would highly suggest reading it though. Here.

That was your warning! Now we’re getting into it. Today, we will be going over inference, alignment, and evaluation in AI (which will make sense soon).

Sections will be:

I. What is Inference

II. Alignment After Training

III. Evaluation: How Outputs are Judged

IV. Limits

V. Fin

I. What is Inference

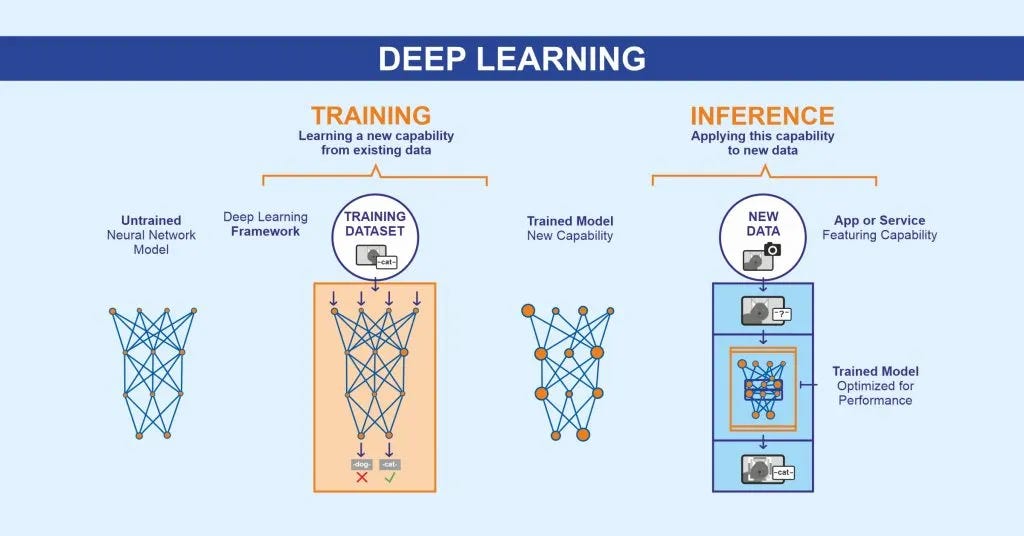

So - if you recall from the last newsletter, AI training involves all the things we discussed last time. Backpropagation and gradient descent, etc. It is a costly and lengthy process and that’s how AI learns/is trained. The next step in the process, after these models are built and trained, is inference. What is inference, you ask?

Excellent question. Inference follows training. For example, inference is a process by which AI comes to conclusions on its own with brand-new data. This is actually the goal with machine learning models, AI that can come to its own conclusions without knowledge of any desired outcome.

For example, AI inference would be AI being able to predict the ending to a film without prior knowledge of the film, based on related but not identical data. Another way to frame this is, how does AI operate at application runtime without previous experience in its exact task?

(taken from xpressoai’s article, describing the difference between training and inference).

Simply put, inference is when you take your hopefully well-trained model and take it out for a spin. You’re trying to test out if your model can actually do what it’s asked, ie, can it solve problems. You’re past the feeding it data to teach it, and you’re into the looking at the outputs stage. The best-case scenario is it doesn’t hit any curbs - it just glides smoothly. This is often not the reality, as models can be confidently wrong, which, if you’re a longtime ChatGPT user or any generative AI chat service user, you might be aware of.

Inference is the model in use; we evaluate its behavior with tests. We are basically testing it to see how it will react in a new scenario with new data.

The real kicker here is that inference is the simple part. Training is the heavy lifting here, with all the backpropagation, gradient descent, and weight tweaking. Inference? That’s just a forward pass. You hand the model some input (text, image, code), it turns that into numbers (embeddings), runs those through its layers, and spits out an output distribution or a probability cloud of “what should come next.” From there, it picks the most likely continuation (or inference).

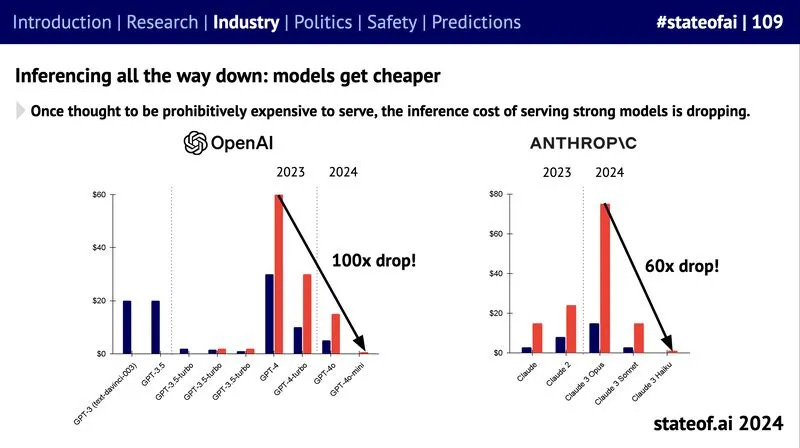

The good news? Inference is getting dramatically cheaper. As models improve and infrastructure gets optimized, the cost per query has fallen off a cliff. OpenAI saw a 100x drop, and Anthropic a 60x drop in just one year.

(taken from the State of AI 2024).

As we discussed last time, these models don’t actually know anything, but they perform knowledge with dazzling mimicry. Inference, as with most of this stuff, is very much an emperor’s new clothes illusion; there is no secret knowledge that these models have in their ‘brains’, they mimic thinking, but they aren’t thinking. They have relational understandings of their data and can thus draw inferences, so this is actually an elaborate form of mapping patterns. What we see with inference is either confident inaccuracy (hallucinating with conviction) or perhaps the correct answer.

The question we have when we are in our inference phase with our models is not whether the model knows the answer. Our model doesn’t know anything! We are actually, semantically, asking a different question: can our model rise to the task of providing useful outputs when our input data is different?

Inference, thus, can reflect our reality quite quickly; at best, you see the fruits of training labor - the model works and convincingly provides the correct outputs on our new data when exposed. However, at the worst, we are reminded that these models are just stochastic parrots in crafty garb.

II. Alignment After Training

While inference is where we take our inputs and see what our outputs are, alignment is how we ensure those outputs are useful, safe, and acceptable. Alignment is basically a set of guardrails to keep our models from going off the deep end.

If you’ve ever asked ChatGPT a question that its alignment protocols have forbidden it from answering, that’s real-time alignment at work (which can be annoying).

There are a few different ways this alignment gets built:

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT).

At first, researchers take a pre-trained model and fine-tune it on curated datasets of “good” behavior, think hand-picked Q&As, explanations, and polite responses. This gives the model a baseline sense of what’s preferred.Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

Next, the model is trained to rank outputs. Humans score which answers are better, and the model learns a “reward model” that nudges future generations toward preferred responses. That’s how chatbots became less blunt and more conversational.Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) & friends.

A newer approach skips the middle step and directly optimizes the model using preference comparisons. It’s cleaner, faster, and often less finicky than RLHF.

But alignment doesn’t just happen once during training; it’s often layered on top of inference. When a model produces a probability cloud of possible outputs, alignment systems act as filters, rerankers, or steering mechanisms. In practice, this means:

Certain tokens or phrases are down-weighted or blocked.

Responses are reranked so “harmless” or “truthful” ones rise to the top.

Additional safety models may run in parallel to catch toxic or unsafe content.

So alignment and inference are intertwined: inference gives you all the possibilities, alignment decides which ones actually make it to the screen.

Of course, like everything else in life, alignment isn’t free. The more rules you put in place, the more likely you are to clip the model’s wings. A highly aligned model might refuse too often, become overly cautious, or feel a little “vanilla.” On the other hand, a loosely aligned model might be more creative and raw, but also more likely to generate harmful, biased, or plain unhinged outputs.

This tension is baked into every chatbot you’ve used. The balance is tricky: safety without sterility, creativity without chaos. Companies are constantly tinkering here, deciding whether to lean toward compliance or user delight, and usually both at once.

And then there’s the bigger question: whose values are we aligning to? Alignment isn’t just a technical exercise; it’s a cultural and political one. Alignment is also about value pluralism: different communities define ‘safe’ and ‘acceptable’ differently, so global systems need cultural alignment rather than a single universal setting, which makes any global AI deployment an incredibly messy business. Our epistemologies are all informed by our own cultural contexts.

So alignment after training is not just about guardrails for inference. It’s about embedding human choices, sometimes subtle, sometimes more heavy-handed, into the pipeline between raw probability and polished response.

III. Evaluation: How Outputs Are Judged

Evaluation is exactly what it sounds like: it’s just grading our outputs against our respective rubrics.

On one side, we have objective metrics. These are neat, mathy, and don’t require a human in the loop. For example:

Perplexity: measures how well the model predicts the next token (lower is better).

BLEU scores: compare generated text against reference text, standard in translation.

Win rates on benchmarks like MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) or BIG-bench.

These numbers give us a sense of statistical competence, but they’re a bit like grading an essay on spelling and grammar alone. Correct, but not the whole story.

On the other side are subjective metrics: humans judging whether an answer is helpful, safe, or makes sense. This is where “red-teaming” comes in, people deliberately try to break the model by asking weird, adversarial, or even malicious questions. If the AI holds up, it passes; if it cracks, back to alignment class it goes!

Determining Good

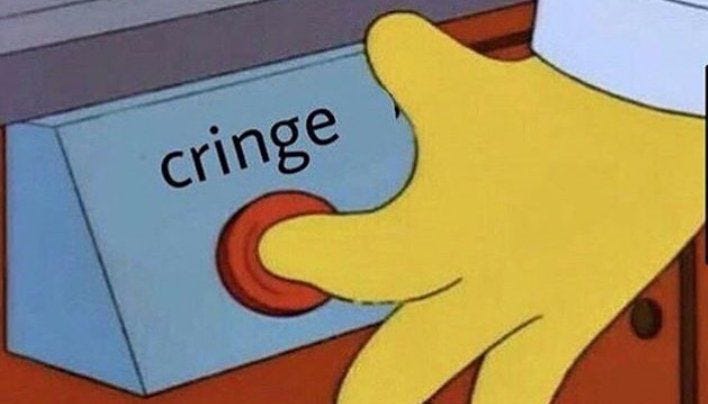

One of the hardest parts of evaluation is deciding what counts as “good.” For factual tasks, truth is relatively easy to check. Does the model know the capital of France? For creative or open-ended tasks, it’s trickier. Is a suggested text message “cringe”? Depends on who you ask. And even for more complex factual tasks, models can hallucinate so fluently that evaluating truth requires careful fact-checking against multiple external sources.

This is why many labs now combine automated evaluation with human oversight, building layered eval suites. For instance, models aren’t measured just on accuracy, but also on fairness, calibration, and robustness. Evaluation is expanding from “did it predict correctly?” to “did it behave responsibly, across a wide range of scenarios?”

IV. Limits

And like the good academic I am, I will turn to the limitations of these models now. On the surface, the narrative arc sounds neat: train a model, run inference, align it, evaluate it! Yet this outwardly simple process is not actually that simple. The limits of today’s AI are everywhere, and they show up most clearly after training.

1. Hallucinations

Models can generate answers that sound brilliant but are factually false. They don’t know, they predict. That means even aligned, well-evaluated systems can still confidently tell you that Paris is the capital of Italy. Evaluation catches some of this, but never all of it.

2. Fragile Alignment

Alignment is never perfect. Models can be “jailbroken” into ignoring guardrails, or they may over-correct and refuse harmless queries. The balance between creativity and safety is fragile, and adversaries often find the cracks faster than researchers can patch them.

3. Cost and Latency

Inference may be cheaper than training, but it’s not free. Serving billions of queries daily burns serious compute, which means environmental costs and financial ones. Optimizations are helping (see the 100x+ drop in inference cost), but scaling remains a ceiling.

4. Evaluation Gaps

Even the best evaluation suites can’t measure everything. Fairness, truth, creativity, safety, these are very human concepts. Red-teaming helps, but evaluation will always lag behind clever prompt engineering and novel attack surfaces.

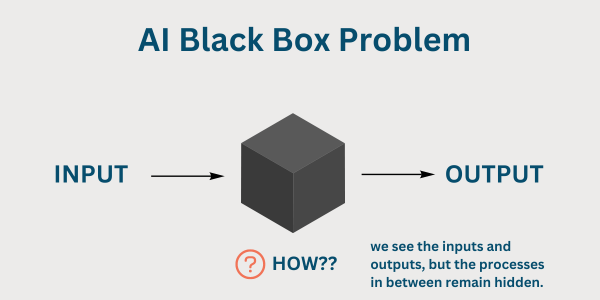

5. The Black Box Problem

We can measure outputs, but we can’t really peer inside. We know the weights, but not exactly what concepts are encoded. Interpretability is advancing, but for now, we live with systems that behave in ways we still can’t fully predict or explain.

(taken from The AI Black Box: Why Cybersecurity Professionals Should Care).

Takeaway

The limits of AI after training are not just technical quirks; they’re fundamental to AI. AI is impressive, but we are still tinkering with tools that have aspects of them entirely beyond our immediate understanding.

V. Fin

That’s actually it for this one! Hopefully, that was informative! I’ve included a laundry list of interesting reading + sources below for the super curious readers of mine.

Next time, we’re going to get a lot further into one of the most interesting parts of AI to me, which is the moral relativism around AI alignment.

Thanks for reading.

Until next time. Bye.

Works Cited / Further Reading

Bai, Y., et al. (2022). Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with RLHF. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.05862

Christiano, P., et al. (2017). Deep Reinforcement Learning from Human Preferences. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03741

Cloudflare. (n.d.). AI inference vs. training. Cloudflare Learning Center. https://www.cloudflare.com/en-gb/learning/ai/inference-vs-training/

CRFM. (2022). Holistic Evaluation of Language Models (HELM). Stanford CRFM. https://crfm.stanford.edu/helm/

Guo, H., et al. (2024). InferAligner: Inference-Time Alignment for Harmlessness through Cross-Model Guidance. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.11206

Hendrycks, D., et al. (2021). Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.03300

Holtzman, A., et al. (2019). The Curious Case of Neural Text Degeneration. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.09751

IBM Research. (2023). AI inference explained. IBM Research Blog. https://research.ibm.com/blog/AI-inference-explained

Ji, Z., et al. (2023). Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.05922

Kaplan, J., et al. (2020). Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361

Olah, C., et al. (2018). The Building Blocks of Interpretability. Distill. https://distill.pub/2018/building-blocks/

Rafailov, R., et al. (2023). Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.18290

Röttger, P., et al. (2023). Red Teaming Language Models with Language Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.19710

Srivastava, A., et al. (2023). Beyond the Imitation Game Benchmark (BIG-bench). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04615

Zhang, C., et al. (2025). Almost Surely Safe Alignment of LLMs at Inference-Time (InferenceGuard). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.01208

Zhang, S., et al. (2023). Language Models are Multilingual Chain-of-Thought Reasoners. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.11793

Zou, A., et al. (2023). Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.15043